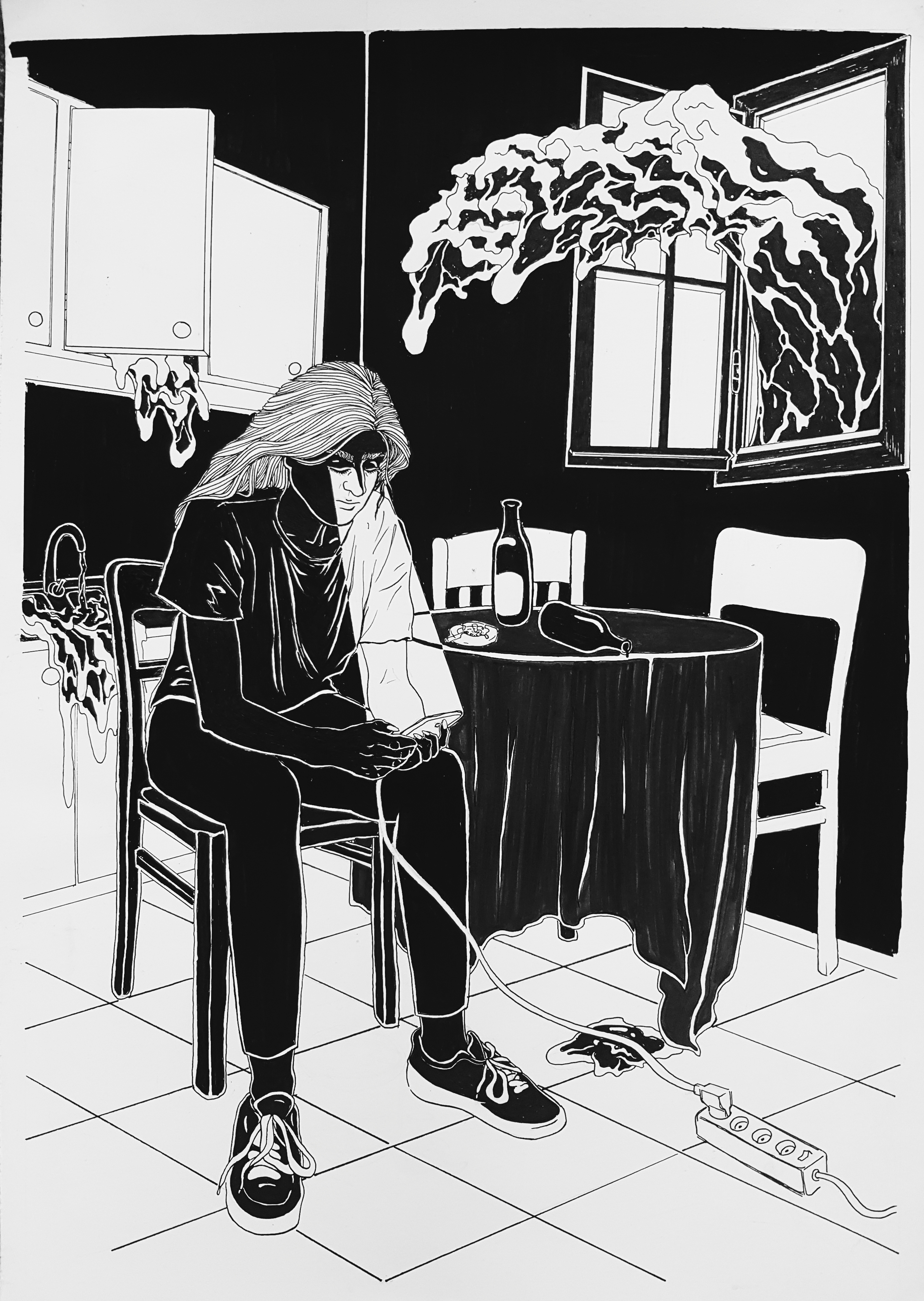

Melancholic future

text: Magdalena Sabatowska

graduate of product design at Central Saint Martins in London

graphics: Klaudia Opoka,

student of Graphics at Pedagogical University in Cracow and Intermedia at the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow

reading time: about 10 min

// Rapid growth of digital platforms has an undeniable impact on mourners and continuously provokes them to channel their grief online, therefore depriving them of a tangible ritual.

Can design stimulate questions about the future of grieving scenarios?

One of the greatest challenges of being human is dealing with the grief caused by the death of a loved one.1 Grief, in all its’ terror and uncertainty, is unavoidable, forcing one to ponder over their own mortality and face conversations that are often considered taboo. Nonetheless, it can be a transformative experience and the impact it has on one’s life might (surprisingly) be a positive one. Freud2 takes that notion to the extremes, advocating that a person must endure a period of grief that eventually results in the capability to relinquish one’s emotional attachment to what has been lost. It is within this process that the mourning rituals would normally take place.

However, looking at approaches to grief in the present day, we are able to observe that these rituals are vanishing.

// One of the most recognized reasons is the expansion of social media as grieving sites and rising unease surrounding conversations about death in real life.

Mourners are more inclined to share their grief online than ever before and this practice raises alarming responses from researchers and community alike. Looking at this phenomenon by analysing past tendencies towards rituals, memorabilia and the designer’s input in grieving scenarios, a question comes to mind: can design practice engage in creating new rituals and restore the tangibility of grief?

1. Castle Jason, Phillips Willam L., Grief Rituals: Aspects That Facilitate Adjustment to Bereavement , 2003, p. 41..

2. Freud Sigmund, On Murder, Mourning and Melancholia, 2005.

3. Kübler-Ross Elisabeth, On Death and Dying, 2009.

4. Freud Sigmund, On Murder, Mourning and Melancholia, 2005, p. 205.

Rituals of grief.

In her ground-breaking book, On Death and Dying3, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross proposes that there are five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Most of them are associated with a ritual that one has to undertake in order to facilitate the grieving process. South Korean designer, Eun-Hae Kwon, has explored this concept and designed a nondenominational architecture model, The Gates of Mourning, applied in the cemetery for those who are dealing with grief. Different gates allow for a different emotion to be experienced, therefore leaving the mourner in control but also creating a liberating environment. Her idea develops into an immersive experience and bends the traditional perception of a cemetery as a place to mourn, in turn trying to make it space where the grief is gradually becoming a part of life.

The grieving process, quite literally “the work of mourning”, is a term originally invented by Sigmund Freud, which indicates that suffering should be a normal part of grief and, in order to be free of the desire to have the deceased back, each single one of the memories bound to that person should be brought up and inspected, liberating the ego and preparing the mourner to move on4. Freud’s idea is not that we should abandon all the memories of the dead, it is quite the opposite. Through, oftentimes painful, the ritual of remembrance one is able to familiarize grief and live alongside it instead of being consumed by it.

And what exactly do we mean by grief anyway? One of the steps in overcoming fear is calling it by its’ name; in this case, the word ‘grief’ has its’ roots in Latin, translating as ‘burden’. This creates quite an evocative image, suggesting that when we grieve, we are carrying the burden of sorrow.5; This burden is something that Mia Cinelli, an

5.Castle Jason, Phillips Willam L., Grief Rituals: Aspects That Facilitate Adjustment to Bereavement, 2003, p. 42.

6.Williamson Caroline, Get Comfort From an Object That Hugs You, 2015.

7. Castle Jason, Phillips Willam L., Grief Rituals: Aspects That Facilitate Adjustment to Bereavement, 2003, p. 50.

American designer, has looked at quite literally while creating The Weight - an object that can hug us whenever we want it to. The Weight offers deep pressure and helps in getting rid of anxiety and stress that often come with loss. In preparation for the project, Cinelli has researched the effects of weighted blankets in occupational therapy practices to help relieve stress, anxiety, inability to focus, autism spectrum disorders and sensory processing disorder. Consequently, its’ typology represents the symbolic burden of grief itself. As it simulates the gesture of a hug from behind, once you feel calm you can literally take the weight off your shoulders.6

Although one can never cease to grieve definitively, the burden of grief can be substantially abolished through mourning rituals. Visiting a grave, celebrating with a feast, displaying photographs of the departed or visiting places that were once significant to them are amongst the most prominent ones. These rituals serve an important survival function by helping to maintain important social bonds but their fundamental motive is an intention to honour not only the loved one, but also one’s connection to them.

// Through the tasks of Freud’s grief work, mourners can “continue to develop their relationship with the deceased by integrating memories into their current lives and relationships”.7

This process in itself is cathartic and reduces the sense of alienation.

9. Lewis Clive Staples, A Grief Observed, 2015, p. 3.

10. de Botton Alain, Religion for Atheists, 2013, p.14.

On the contrary, an utterly different argument is proposed by C. S. Lewis who, being a widower himself, established a personal testimonial illustrating the experience of bereavement after his wife passed away. Lewis shows a side of grief that is the least spoken about – absolute despair. In this state “grief is like a long valley, a winding valley where any bend may reveal a totally new landscape”.8 According to him all the rituals of sorrow – visiting graves, keeping anniversaries etc. – resemble a mummification, they emphasize the “deadness” of the deceased. He offers neither solace nor solution to those in grief, which distinguishes him from other mentioned authors. Whilst others recommend the outdoors and social encounters to ease the pain of losing someone, C.S. Lewis is unconditionally paralyzed with his grief which he later states with a famous sentence “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear”. 9 One should take into consideration the impact of religion or lack thereof on the mourning customs. It is worth remembering that Lewis as a devout Christian was equipped with a set of explanations and rituals already in place, even if they existed there only for him to question. It is not the case for the growing population of atheists, whose way of mourning is practically non-existent. As highlighted by Alain de Botton “secular society has been unfairly impoverished by the loss of an array of

practices and themes which atheists typically find impossible to live with because they seem too closely associated with (…) ‘the bad odours of religion’.” 10

With substantial growth of the atheist population, a change in the way we grieve and how we facilitate the grief of others is much needed. This proposes an objective for the design practice to attempt to respond to the needs of grieving atheist society. Designing secular mourning rituals could empower the future mourners and promote a conscious and accessible debate on the topic that is still considered taboo.

Inspiration can be drawn from death positive movement, specifically The Order of the Good Death which focuses on encouraging open conversation about death and grief. It is their belief that talking about and engaging with inevitable death is not morbid but displays a natural curiosity about the human condition.

Another debate about what it means to grieve in the 21st century has been picked up by a rapidly growing alternative funeral movement. Berlin-based funeral company Lebensnah and Karen Admiraal, a freelancing funeral director, help bereaved families to think beyond the dimensions of a traditional funeral and establish a more personal experience – intended not only to celebrate the person they have lost but to support their own mourning process. Alternative funerals provide a way for the bereaved to adjust the ceremony to their (and the deceased’s) needs and make it more of a celebration of their life than mourning for their death. Families and friends are often suggested to build and decorate coffins and urns themselves. Although this hands-on approach might not suit everyone, it has proven to be empowering and benefits the bereaved in the long term.

11. Hallam Elizabeth, Hockey Jenny, Death, Memory & Material Culture , 2001, p. 2.

12. Pearce Susan, Interpreting objects and collections , 2006, p. 196.

13.Turkle Sherry, Evocative Objects , 2011, p. 228.

14. Proust Marcel, Remembrance of Things Past. Vol. 1: Swann’s Way & Within a Budding Grove , 1982, p. 51.

The significance of memorabilia.

Preserving mementos is another way to honour loved ones and plays a significant role in coming to terms with loss . It can be said that memorabilia are an inseparable part of a grieving process, they remind us of the death of others and of our own mortality.11 This opinion oscillates between the notion of consciously collecting objects that belonged to the deceased and, on the other hand, a much more unintentional encounter with personal possessions that were left behind, oftentimes comprised of prosaic items that we wouldn’t necessarily collect.

The first group is identified as souvenirs, samples of events which can be remembered, but not relived. They exist in order to authenticate the narrative in which the bereaved talk about their grief. Therefore they have the power to deny the passing of time and carry the past into the present.

“Souvenirs, then, are lost youth, lost friends, lost past happiness; they are the tears of things”.12

Another approach to memorabilia formulates the term ‘evocative objects’, describing items that can hold the vast structure of recollection. These objects might not necessarily have belonged to the deceased but they possess an emotional link to that person. Evoking that link can be achieved by a variety of factors; through items kept from childhood, smell of someone’s perfumes and cooking being the most common of them all, it draws our attention to the fact that “[an] object can hold an unexplored world, containing within it memory, emotion, and untapped creativity”. 13 That note is even further emphasized by Marcel Proust and his, now acclaimed madeleine cake. In the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past Proust finds himself tasting a spoonful of madeleine when suddenly he is overwhelmed by a returning memory that this cake has evoked. He concludes that “…after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring (…) remain poised a long time”.14

In the recent years designers have engaged the topic of grief into a range of different practices, making grieving process more approachable and aiming to familiarize their audiences with the inevitability of their own death. It demonstrates that the discussion about mortality is not something that design should refrain from.

Some of the most prominent and startling projects involve the use of human ashes to create objects that facilitate mourning. Geraldine Spilker in her project Memento – After Time Elapsed has invented and tested a method of combining ashes with resin, making a tactile product from cremated remains. The object – in the shape of a spinning top - is entirely biodegradable, so the ashes can be returned to the earth when the bereaved is prepared. Meanwhile, it is possible to hold, caress and carry around the ashes. As described by Spilker herself: “It moves away from the static existence of an urn, to a gentle dynamic of picking up, touching, playing and observing.”. 15

15. Treggiden Katie, Geraldine Spilker combines ashes with resin to create mementos of the dead , 2014.

16. Jones Jessica, Lisa Merk's tactile mini urns give mourners one-on-one time to say goodbye , 2017.

17. Hallam Elizabeth, Hockey Jenny, Death, Memory & Material Culture , 2001, p. 208.

18. Verde Tom, Aging Parents With Lots of Stuff, and Children Who Don’t Want It, 2017.

Another project that involves cremains (cremated remains) are Lisa Merk’s tactile mini urns which serve as an anxiety-reducing alternative for the funeral ceremony. They are filled with a symbolic part of ashes of the deceased and mourners can choose to hold them in their hands or include them in the bigger urn that might be buried later. “Since funerals are very emotional and stressful events I wanted to provide something for the mourners that they could hold onto or even share their sadness with, at least for the moment of the service.”. 16

This project creates an image of a funeral that steps away from the traditional ceremony. It gives each of the mourners a chance to have a part of their deceased with them for the ritual and leaves an option for burial or further keeping of the ashes.

On the other hand the influence of consumerism on material cultures of death and traditional rituals has been widely recognized.

// Mass merchandising and disposable character of consumer goods have noticeable effects on memorials and the fast-paced world we now live in has significantly changed the way we grieve. “The time spent remembering the dead is drastically reduced in later twentieth-century consumer culture”. 17

Design thinking in terms of personal memorabilia needs to accommodate the fact that we live faster and the burden of disposing of our loved one’s possessions is often an unwanted one. “As baby boomers grow older, the volume of unwanted keepsakes and family heirlooms is poised to grow — along with the number of delicate conversations about what to do with them.”. 18Future generations, more inclined to live in shared and compact spaces, might experience plenty of difficulties with the sheer bulk of commodities that they will inherit after their relatives pass away. Firstly, because of the lack of space to physically distribute it in but also because amidst the overwhelming qualities of souvenirs they might come across an unexpected or difficult discovery.

Death instigates conversations regarding what should be kept in the face of loss and challenges mourners to determine how they would like to remember their loved ones. Ironically, memorabilia and the emotional value they carry can be both beneficial in the recovery from loss but they can also reinforce the painful feelings associated with death.

This raises a question whether design’s task is to endorse the collecting character of the deceased or rather propose a reassessment of ways in which mourner could dispose of the memorabilia without guilt. More importantly, however, designers should speculate how afterlife of the products they create can be used to enhance and support the grieving process of the bereaved.

19. Nansen Bjorn et al., Social Media in the Funeral Industry: On the Digitalization of Grief, 2017, p. 73.

20. Brubaker Jed R. et al., Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning , 2013, p. 156

21. Frankel Richard, Digital Melancholy, 2013, p. 14..

22. Bollmer Grant David, Millions Now Living Will Never Die , 2013, p. 145.

Digital mourning.

The practice of grieving online is constantly growing, with social media sites “increasingly incorporating features to enable the bereaved to commemorate their dead and share their emotions associated with loss”. 19 Facebook creates a new setting for death and grieving - one that is broadly public with an ongoing integration into daily life. Users have yet to establish norms around death on social media but there are two sides of the argument clearly emerging.

The first one insists that social media provide mourners with new ways of talking about grief, therefore making it less painful and allowing other users to share sympathy and offer help. The feeling of alienation, oftentimes associated with grief, can be avoided with the help of digital platforms and sustaining online profiles that belonged to the deceased can create a memorial for those in need of “contact” with their loved ones. It eases the pain of those involved in grief and causes them to feel as though their messages can still be received.

“While, on the one hand, Facebook is seen as too casual a medium for a weighty topic such as grief and grieving, it simultaneously provides people with ways to engage with the dead and fellow mourners in ways unlikely in conventional grief practices.”. 20

However, this argument is overwhelmingly defeated by those against cyber mourning, it being a response to the social media’s population that refuses to let anything pass away. Every status, photograph, and comment is preserved, thus creating a memorial of us while we are still alive. And when we eventually die, our relatives and friends can visit our profile constantly as our digital selves are still present. “This creates a terribly confusing, masochistic state of mind, a melancholic stance where the bereaved desperately seeks to keep the person alive through devoted attentiveness to its manifestation in virtual space”. 21 In this scenario the grieving can go on eternally, preventing a sense of closure to occur for the mourners.

Two-dimensional, digital approach to mourning flattens our emotional investment in the other person’s loss and makes it more trivial when displayed alongside other social media content. Zadie Smith argues that “the interactions with the deceased online are symbolic of a more generalized devaluation of human life”. 22 She suggests that the younger population, so-called generations Z and Y, growing up in a social media savvy environment will gradually find it more problematic to distinguish Facebook pages from living people, treating one like the other and leading to an inability to grasp the meaning of death when someone actually dies.

23. Brubaker Jed R. et al., Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning, 2013, p. 157.

24.Morby Alice, Neri Oxman's Lazarus death masks visualise the wearer's last breath, 2016.

25. Frankel Richard, Digital Melancholy, 2013, p. 19.

The phenomenon of cyber mourning shields us from the reality of contingency and death and oftentimes creates a narcissistic orientation towards loss. Condolences or even notification of a loss posted online have a rather selfish task of presenting the mourner in a better light. Moreover, it creates a sense of discomfort - for those who prefer more private forms of mourning, posts written by their friends/ followers can be seen as intrusive; and for others the shock of discovering the death of a friend via social media leads to questioning what is a “proper way” to honour them. 23

Design should be able to respond to grief with approaches that will appreciate digital functions but which won’t be based solely on them. Such is the collaboration between Neri Oxman and the MIT Mediated Matter group which resulted in a set of 3D-printed death masks, designed to enclose the wearer’s last breath. The “air urns”, as described by Oxman, are modelled on the facial features of the deceased individual, for which the team has invented a custom software creating high-resolution and complex shapes based on data. 24 This, very elaborate project, is based on a primitive idea of death masks. The masks, originally made from plaster or wax, were supposed to immortalize features of the deceased which would allow the mourners to keep them alive through their memories. Oxman’s intention is the same however, she places her scenario far into the future which allows for the use of new technology.

Mourning online is an option but it is not enough to process the overwhelming sensation of grief. That is one of the reasons why tangible rituals could be reassessed to fit the needs of bereaved in the modern world. They could also guide the mourners through Freud’s “work of grief”, as opposed to online mourning which leaves that process eternally unfinished. In the latter case, “we are vulnerable to a melancholic haunting; where the self’s relationship to the world of living objects is hindered by its mental absorption in a world of absent objects, a reactivation of the dead.” 25

// Ultimately, what ends the period of grief is the understanding that, while our loved ones passed away, we are still alive.

Digital mourning blurs that distinction, preventing the bereaved from moving forward while a tangible ritual, although emotionally draining at times, endorses that thought and liberates the mourner.

Conclusion.

It is clear that the culture of mourning rituals has thrived in the past however, it is now facing a serious turning point. The digitalization of our daily life and a growing population of atheists are the biggest influences contributing to the decline of mourning customs in the present-day. These two factors alone have the power to make grieving rituals obsolete, simply because they do not fit the needs of either the atheists or the cyber-mourners. The task of designers in the future is to decide how to engage in the topic of grief that will facilitate and understand this ever-changing environment; it is an important task indeed.

As it may be, design cannot change the way people will grieve immeasurably, be it online or in the real world. It is a personal process that every one of us will have to go through and as such, it is equipped with our own understanding of mortality, our intimate stories, and memories of the deceased.

That being said, as one of the objectives, design could provide choices for those that are hesitant about sharing and processing their grief digitally as well as those who, due to the lack of religious beliefs, are struggling to find a way to honour their loved ones.

Consequently we are able to notice that, despite an overwhelming popularity of social media platforms, when it comes to sensitive matters people still value a sense of materiality and closeness. This sense can be a starting point for design practice in creating more evocative, meaningful speculations about the future of grief and eventually providing a tangible solution.

Finally, mourners of the future might, in the end, choose to share their loss online and the author cannot blame them or even try to advise them otherwise. After all, a threat of unfinished ‘work of grief’ which, as suggested by Freud, leads to a life of melancholy and despair, might be enough to encourage them to investigate other options. It is very much likely that with the help of design, tangible grieving tradition can flourish again in a new and unexplored environment and with its’ growth we will be able to observe a coexistence of the physical and digital world.