project's authors:

Nicholas Gervasi,

Adjunct Assistant Professor at Dept. of Architectural Technology, CUNY New York City College of Technology and Project Architect / Head Researcher in Terreform ONE

Kristina Goncharov

Master of Science - Smart Cities and Urban Analytics at UCL / the Director of Strategy and Business Development at Terreform ONE

reading time: around 15 min

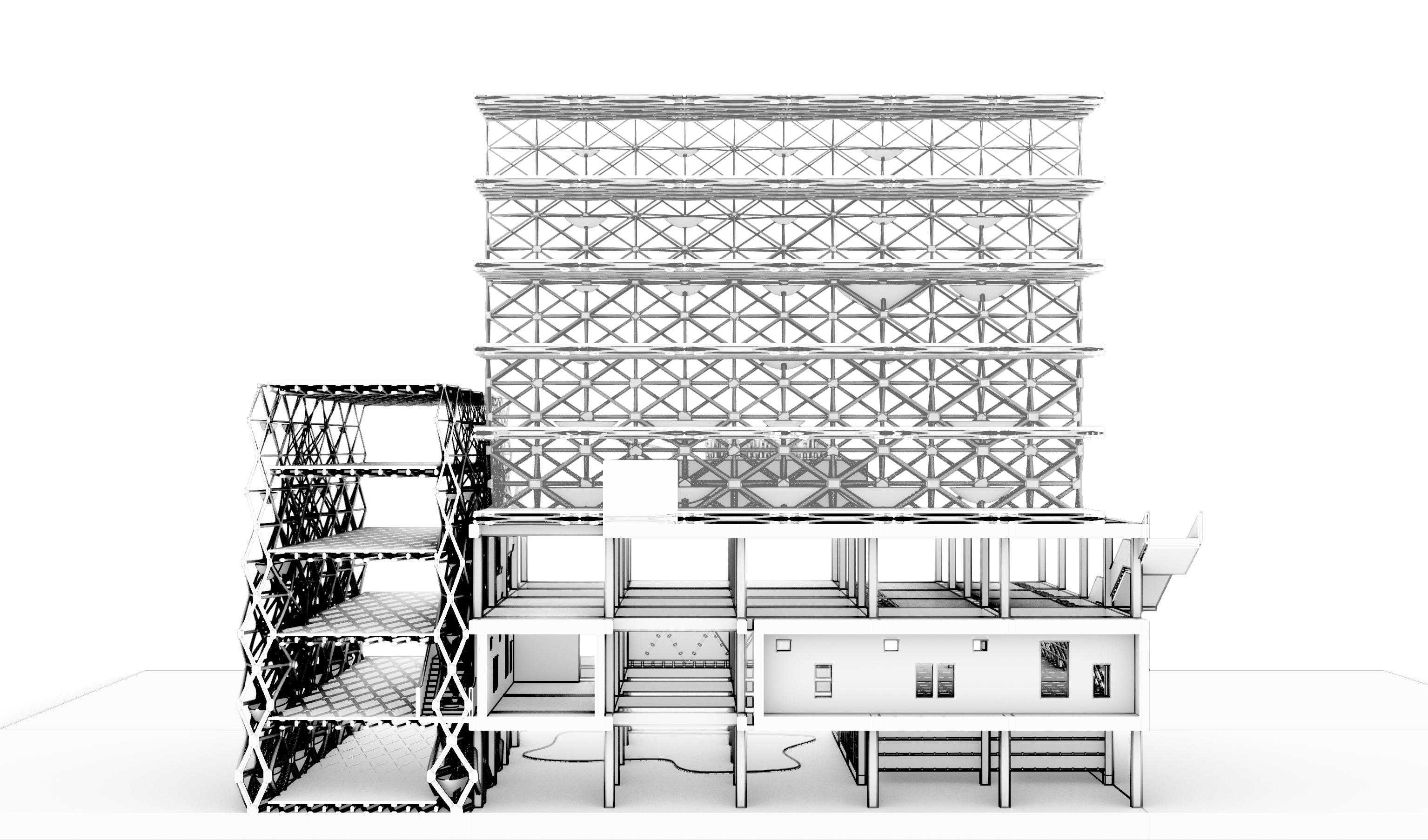

As new housing models, materials, and methods continue to spawn within the theoretical and built projects of architects and allied fields, we maintain that regenerative design can be taken further by a lifecycle framework applied to the occupants as well as the building materials. Focused on upward mobility and the architecture that can drive it, this proposal argues for the integration of work and living on the same campus in order to facilitate not only sustainable housing practices but also sustainable economics. Granting occupants more design decisions and construction knowledge, the resultant form will better represent evolving needs and affinities. We believe that urban, suburban, and to a lesser extent rural housing does not design for changed use patterns, disassembly, or non-traditional living scenarios. Moreover, the occupant has little autonomy to alter their living spaces to their varied desires. Finally adding a layer of human intelligence and mentorship to the site will provide a vessel for skill transfer.

The Context

Urban developers’ propensity to create monotonous, fatiguing solutions can be seen in abundance globally. For example, in the United States, the fierce urban renewal schemes backed by Robert Moses in the 1950s proved a lack in understanding of the residents for whom the housing was being built. The schemes segregated the financial strata of the communities and enhanced negative stigmas towards those who resided within. Furthermore, the disconnection between housing and public activity created urban lulls and zones of disengagement.

The ladder of Citizen Participation, developed by Sherry Arnstein, who was an author and worked in the U.S. Department of Housing, Education, and Welfare (HUD), aimed to tackle the lack of understanding explored above. From her seminal article, the first rung (i.e. the least ‘participatory’ measure) is Tokenism – the participation of individuals in question is only symbolic and proves no weight in final decision-making situations. Developments who follow Tokenism-based initiatives, often cause more disruption than the benefit they bring. We have all witnessed Tokenism whether it be community meetings that bear no significance to project goals or false predictions about how user groups will occupy a space.

Our proposal will focus on the city of Charlotte, North Carolina and its larger context of Mecklenburg County. This region embodies the challenges outlined above yet provides opportunity for re-conceived housing. Peering into the future, economists anticipate an influx of over a half million residents in Mecklenburg County by the year 2030. A significant worry for struggling locals, approximately 190,000 of which currently reside in unstable housing conditions. Since the release of the ranking in 2018, a number of local initiatives have been created and interest into sustainably developing the county has increased. However, those developing affordable housing solutions for the region are, as often seen elsewhere globally, failing to fulfil the true requirements for affordable housing and social housing schemes. At current rates of improvement, the future runs counter to the positive rhetoric supposedly driving these changes.

The Counter-Context

Often affordable housing schemes lack stable, social support channels, are poorly maintained and residents have little say in the matter – by nature these environments drawback the opportunities of their residents. When these developments should be about fostering professional and personal growth of their residents. Developments must be positioned as homes for entry level professionals, teachers, engineers, public sector workers, economy drivers. To improve the standards of those who rely on affordable housing, the community as a whole must pivot its manner of thinking. To truly change the vicious cycle of affordable housing solutions, an approach which focuses on the development of the resident’s social and financial gains, promotes circular economies of knowledge, skills and opportunities and is viably able to provide for higher standards of living is required.

Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are a good example of this new economic model. Here, the community are the stewards and owners of the assets on-site; they play a key role in managing resource distribution throughout the site, and in-turn, are re-instated with full ownership of profits harvested by the site. Such initiatives permit for optimal community participation and fulfil the highest rung on Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation – Citizen Control. To achieve this rung, citizens must have full control over policies and plans affecting the site and hold leadership over the conditions of which amendments may be made by aliens to the site. CLTs significantly supersede typical government-backed schemes, which stand within the Nonparticipation and Tokenism ranks (rungs 1 and 2 respectively).

Combined with ownership of the assets and upward mobility options, regenerative design is the next overlay to this framework for affordable housing. Beyond sustainability, regenerative design is net positive impact and operates on the abundance model recently elucidated in The Upcycle by William McDonough and Michael Braungart. This model, an example is the cherry tree and its leaf and fruit dispersal systems, is characterized by entities that produce nutrients beyond their own needs in order to foster ecosystem health. Allocating their own resources to provide for other species rather than their own optimization, they are critical regenerators of their regions. Furthermore, by strengthening their host ecosystem, they imbue resilience into the system that can ensure their own survival later on. This creates a positive feedback loop that mutually benefits the tree and the ecosystem. We apply this method to the eco-house by Instead of building materials transported across great distances to the site, they are grown in situ. The architecture wraps and frames these groves of supplies.

Sim Van der Ryn emphasized the importance of living systems in regards to the health and wellness of humans. Living in reference to biomaterials and architectural surfaces becoming a vessel for life. Hospital designs provide empirical evidence via patient recovery times of the benefits of greenery integrated into buildings. Practices that have been thoroughly immersed in Singapore across several typologies. He advocates for ecomorphic buildings which “copy the processes in nature and incorporate those into design” versus direct imitation of the forms of nature.

Regenerative design originates with a hyperfocused examination of the site in order to extract a an ecological mechanism to replicate in the architecture. This correlates closely to Ken Yeang’s position that eco-architecture goes beyond simply climate appropriate design interventions but also touches upon cultural cues from that area. Advocating for architects to think about how this drives the form of buildings, again not in a biomorphic manner but in Van der Ryn’s ecomorphic concept, although Yeang proposes it as eco-mimetics. However, both ideologies boil down to flows over aesthetics with the building steering and harvesting its site embedded qualities.

A New Context

We have based our proposal on the typical structure of a Community Land Trust and 3 key requirements outlined in a framework approved by the City Council in 2018 to drive change. The requirements can be seen as follows:

1. Expand the supply of rental and owner-occupied housing

2. Preserve the affordability and quality of the housing

3. Support family self-sufficiency

By combining the managerial-community approach of CLTs and the core requirements of the developments in question, we believe it is possible to turn the tide on engrained social stigmas to such housing solutions. Incorporating economic drivers into the schemes.

Regenerative architecture begins with the human spirit. Housing is where the mind mends itself through thought and sleep. Arguably it is the only typology that activates the unconscious mind. Space that is detached from the temporal permissions offices, public realms, and institutions exert as it doesn’t have an expiration for the occupant.

Eco-homes are traditionally designed for an ascetic or minimalist lifestyle. The root of this symbolism is well intentioned – to encourage sustainable practices and avoid wasteful consumption. To instill a sense of organization and self-reliance with the occupant. In its most ideal state the objective is to transfer the physical tidiness of the space itself to the mind in order to unclutter it. However, this ignores a foundational driver within us to make places our own. To adorn walls with picture frames, place rugs across the floor, and arrange furniture into sequences – all to convey our expression inside the architecture. Although these percepts may appear to operate against one another, minimalism and ornament, they both reiterate our behavioral initiative to reflect or reveal ourselves onto the space around us. Even if it is done inadvertently through carelessness or laziness.

Thus the home is the quintessential place for adaptive changes and evolution during the course of inhabitation. Walls that shift and add space. Roofs that retract and later elongate. Windows and doors to make passageways and reflect new relationships amongst programmatic elements. Floors to step and slope as the landscape grapples with human occupation.

The growth cycle of bamboo creates a new supply of building materials each year. Due to the intrinsic rhizomatic qualities of this grass, each subsequent year the shoots grow taller yet remain the same diameter as before. This subsurface activity, which can be guided by trenches, is the generator for new culms to emerge. With a sixty day growth cycle and innate duplicative traits, bamboo multiplies itself stronger and stronger as the seasons go on. This philosophical connection to a person gaining mental strength through recovery is not to be overlooked.

Eastern practices of preservation, which involve cyclical reconstruction of cultural heritage in order to preserve authenticity of technique rather than of materials, are invoked as principles to inform site evolution. Carpentry skills will be developed in order to rebuild walls, roofs, and floors, as well as expand.